|

От «арабской весны» к азиатским восстаниям

|

Не все волны восстаний приносят перемены, на которые надеются люди. Как наши могут? Как мы могли бы выбрать наши следующие шаги, учась на путях перемен у сограждан мира?

В декабре 2010 года тунисский уличный торговец Мохамед Буазизи поджег себя после того, как полиция конфисковала его товар. Это вызвало «арабскую весну» – масштабное восстание, в результате которого были свергнуты режимы в Тунисе, Египте, Ливии, Йемене и других странах. Тунис перешел к демократии, но в других странах старые державы вновь заявили о себе. Египет вернулся к авторитарному правлению; Ливия, Йемен и Сирия погрузились в гражданскую войну. Во многих странах «арабской весны» условия с точки зрения безработицы среди молодежи, свободы прессы и коррупции сейчас выглядят хуже, чем раньше.

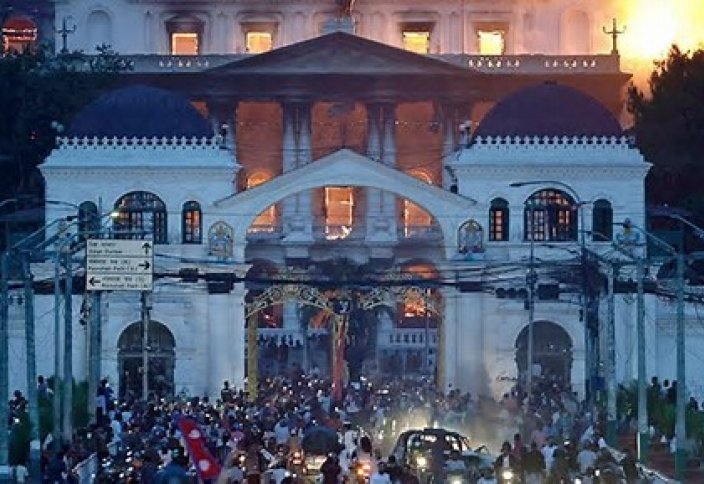

Даже если не оглядываться назад, ранние закономерности очевидны по всей Азии. Ключевые события в Шри-Ланке, Бангладеш и Индонезии вызвали протесты, в результате которых были свергнуты неподотчетные лидеры. Тем не менее, превратить беспорядки в стабильные, мирные общества гораздо сложнее. Одних надежд и эмоций недостаточно; Они должны сопровождаться практическими и реалистичными действиями.

«Молодежные» восстания в Азии

Азиатские молодежные восстания имеют общие черты. Их часто возглавляют студенты и представители поколения Z, выражая коллективное недовольство и требования перемен в городских центрах, движимые призывами к экономическим возможностям, лучшему управлению и реформам. Большинство восстаний не возглавляются партиями, хотя со временем граждане разных партий присоединяются к этим движениям, разжигая насилие, политический тупик, еще больше укрепляя статус-кво, а в некоторых случаях и медленные, но постепенные изменения.

В Таиланде успех партии «Движение вперед» на выборах в 2022 году был заблокирован Конституционным судом — «социально спроектированным» учреждением, находящимся под влиянием армии и промонархических сил, — препятствующим значимой передаче власти. Суд заявил, что партия угрожает национальной безопасности и монархии. Между тем, в Мьянме, после десятилетнего демократического эксперимента, военные устроили переворот в 2021 году, сокрушив движение под руководством поколения Z и еще глубже погрузив страну в гражданскую войну.

Но разворачивающиеся события после восстаний в Шри-Ланке и Бангладеш показывают уроки, к которым Непалу следует прислушаться.

В отличие от Непала, протесты в Шри-Ланке длились неделями, а политические изменения были скорее постепенными, чем стремительными. Парламент не был распущен. Перед отставкой президент Готабая Раджапакса назначил Ранила Викремесингхе вице-президентом. Позже парламент избрал его президентом. Он правил до выборов 2024 года, которые проиграл. Во время своего президентства Викремесингхе получил чрезвычайный фонд в размере 3 миллиардов долларов от Международного валютного фонда, ввел меры жесткой экономии и оживил экономику. Тем не менее, его критиковали за использование военных для подавления протестов и заключение в тюрьму ключевых лидеров.

Anura Kumara Dissanayake, whose party, the National People's Power (NPP), won the election and replaced Wickremesinghe, has initiated key reforms, notably on transparency and public accountability. His administration has also charged corruption to various senior officials under the Rajapaksa government, including former president Wickremesinghe. Yet the Rajapaksa family remains untouched. Other critical issues like economic stabilisation, inflation and debt restructuring remain challenging. "There is much to deliver," Joseph Maniumpullai, a long-time development professional who works in Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh, said, "public expectation is unrealistically high, and whether the government can last until 2028 [next election] or not is a question."

Bangladesh offers a different perspective on how an interim government can slip into uncertainty and power struggles. Like in Nepal, the parliament was dissolved after Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina resigned and fled the country. The interim government, led by Muhammad Yunus, now wavers between reforms and elections. More than a year has passed, and it still has no clear election date, despite announcing plans for February 2026. The youths who led the protests formed the National Citizen Party (NCP), now part of the government, while Jamaat-e-Islami and others pushed for more reforms first. The army, still deployed and influential, has begun voicing concern over government decisions. The interim administration is mired in a messy power struggle, pursuing retributive politics such as banning the Awami League party. As The Daily Star editorial notes, the government has no shortage of "reform ideas, but the failure to implement them."

History shows that revenge leads to cycles of violence whereas measured, reconciliatory approaches break cycles of violence, help heal the old wounds and build peace.

Gen Z uprising and the way forward

Nepal's Gen Z-led movement is historic, with the public rising against political parties under a democratic system without guidance from established leaders or parties. Two points are crucial. First, it is a homegrown movement. Framing it as externally funded or conspired is a self-defeating rhetoric that undermines Nepal's identity, power and standing at home and abroad. This must stop.

The carnage that unfolded within 15 to 24 hours during the protests demands a transparent investigation. Yet, CCTV footage, party infighting, factionalism and widespread public frustration call for critical analysis rather than blaming "others." Every country faces geopolitical rivalries, and it is up to the government and citizens to understand and manage them carefully. Blaming is easy and unaccountable, whereas addressing internal issues is difficult, messy, but ultimately a responsible thing to do.

Cleaning house, the second point, is about reforming Nepal's political parties. To make democracy and governance work for all, parties must restructure to end their leaders' long-standing hold on power. True internal party democracy would ripple into government, compelling the rigid, traditional bureaucracy to follow and challenging the clientelist ecosystem of corruption. How the interim government paves the way for such reform remains a critical discussion.

For Nepal's transitional government to work effectively, it can draw vital lessons from the Arab Spring and Asian uprisings. Without leadership and parties that genuinely represent the aspirations of marginalised groups, power vacuums can create chaos and uncertainty-a risk that Gen Z leaders and their allies must avoid. Comparisons abroad underline the stakes: Bangladesh's interim government banned the Awami League and stuck in reforms that delayed elections, while Sri Lanka's post-Rajapaksa governments allowed the Rajapaksa-controlled party to contest elections but focused on urgent economic reforms and accountability, avoiding political deadlock. Considering this, how the Susila Karki-led administration manages long-standing political parties and their deep connections across the bureaucracy, civil society and private sector is crucial. Although calls to investigate corruption among senior leaders are strong, the response of mid- and junior-level cadres will likely determine the effectiveness of the transitional government

In the post-Arab Spring period, Tunisia moved towards stable democracy, while other countries descended into civil war or returned to authoritarian rule. Many Asian nations still face structural political challenges, though some continue to make progress. Vengeful and retributive politics may offer immediate relief from frustration, but they can perpetuate cycles of violence and destruction over time. Gen Z has already shown how digital spaces can unite communities around shared concerns. Community-led efforts to restore destroyed public offices and police posts during protests also serve as a powerful reminder that we can still rise from the ashes to reshape our shared past and build a more inclusive present and future. This is what we can and should show to the world.